The Remington Model 11 Sportsman In World War II (Made in Ilion, NY)

Plain, utilitarian, unadorned—those are the words typically associated with standard military-issued firearms of World War II. While some individuals chose to carry more elaborate guns, like the famous ivory-handled sidearms of General George Patton, your average G.I. carried firearms free from unnecessary factory embellishments that would only add to the time and expense during manufacturing. Even functional decorative work, like checkering, is often absent from military guns, despite the undeniable benefit that a firm grip would provide in the mud and blood of combat.

That isn’t to say that such mass-produced firearms can’t be works of industrial art in their own right, but the primary purpose was not aesthetic. On the other end of the spectrum, sporting arms have historically been available with finely wrought embellishments on the wood and metal for the discerning customer willing to pay the extra expense required for the skilled labor needed for the work. On the metal, these extra details often centered around the type of game that the user of the firearm would be likely to take, be it a magnificently antlered stag engraved on a rifle or birds and rabbits on a shotgun.

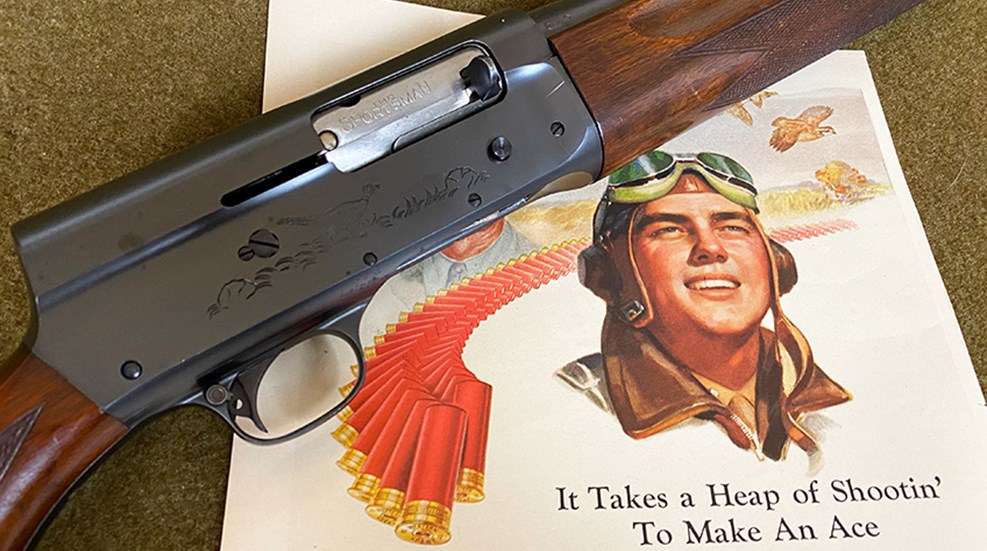

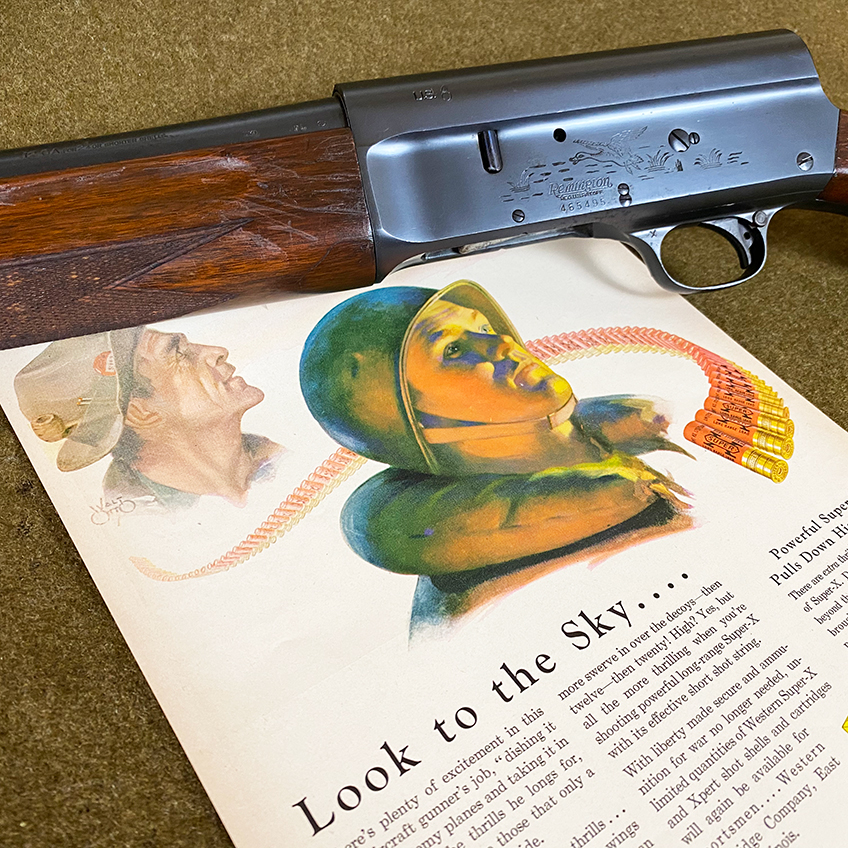

A Photo of the author's U.S. Ordnance marked Remington Model 11 Sportsman.

While the more elaborate guns were aimed at a wealthy clientele able to pay a significant surcharge for the work, even the common man could obtain a moderately embellished firearm at a fair price. One example of a firearm that saw widespread usage in the hands of average hunters is the Remington Model 11 and its variant, “The Sportsman." Introduced in 1905 as a licensed copy of Browning’s Auto-5, the Remington Model 11 was commercially successful and provided hunters with a relatively reliable semi-automatic shotgun to compete with the numerous well regarded pump actions available at the time.

The Model 11 and Sportsman are quite similar to one another, with the most notable difference being capacity. The Model 11 holds 4+1, while the Sportsman only fits 2+1 to comply with hunting restrictions in certain states. Additionally, there are slight dimensional changes to the fore-end, and a different cap tops the fore-end of each variant.

The "game scene" roll mark on the right side of the author's Model 11 Sportsman, a pheasant walking through brush.

As World War II loomed, both came standard with a “game scene” roll stamped on either side of the receiver—a duck in flight over a marshland on the left, and a pheasant walking through the grass on the right. Since these are both animals the shotguns would likely encounter during their service as sporting arms, such marks are fitting, but totally incongruous with standard service markings of plain-Jane military firearm, right?

Normal government contracting standards were thrown out the window after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. Overnight, the nation found itself at war, and in desperate need of arms to support the war effort. Weapons were not only needed for overseas service, but also for training new recruits, and conducting guard duty at all manner of manufacturing plants and other facilities that suddenly found themselves indispensable to the cause of victory.

The "game scene" roll mark on the left side, a duck in flight over a marshland.

Due to this, the government, in the form of the newly established War Production Board, took dramatic action to ensure that enough weapons would be available for defense use. The first, Limitation Order, No. L-55, issued on Feb. 23, 1942 identified that “national defense requirements have created a shortage of shotguns for plant patrol and other local guard duties” and that it was “expected that Government orders for large numbers of 12-ga. shotguns will be placed.”

To address those issues, it ordered all manufacturers engaged in the production of shotguns to convert all facilities capable of making 12-ga. shotguns to that purpose. This didn’t just include traditional “Trench Gun” platforms like the Winchester Model 1897 or Model 12, but also all “single barrel, double barrel, repeating, riot, pump and any other type of shotgun of any gauge whatsoever.”

The author's U.S. Ordnance marked Remington Model 11 Sportsman.

Additionally, any machine or equipment that could be used for assembling or manufacturing a 12-ga. shotgun could not be used for making a shotgun of any other gauge, and the allowable production of shotguns of other gauges was severely restricted. Finally, manufacturers were prohibited from selling, delivering, shipping, transferring or otherwise disposing of any 12-ga. shotgun unless it was transferred to the federal government, state or local governments, sent via Lend-Lease or sold via agreement to specified allied countries.

The War Production Board doubled down only four days later when on February 27, 1942 it issued limitation Order No L-60. This order expanded the stated shortage to include “pistols, rifles and shotguns for use in police work, plant patrol and other local guard duties” and increased the scope of the restriction on sales. Now no person, expect manufacturers, could sell, lease, trade, lend, deliver, ship, transfer or otherwise dispose of any new pistol, rifle or shotgun unless it was to the excepted parties from L-55.

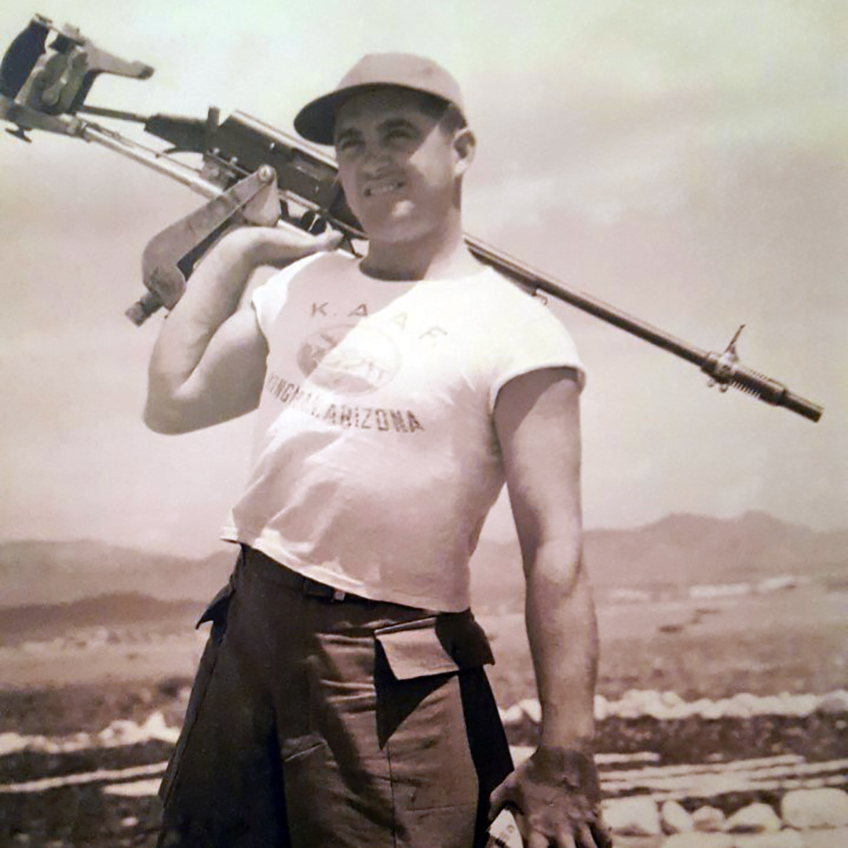

An aerial gunnery trainee posing with a long-barreled Remington Model 11 fixed with a Cutt's compensator, raised aerial sights, and a chassis that simulates an aircraft machine gun mount.

This was also the case if an order was already in transit to the destination or an order had already been placed by an individual with a high “preference rating”. Furthermore, all “dealers, jobbers, wholesalers and distributors” were required to furnish a complete inventory of their rifles, pistols and shotguns to the War Production Board within 45 days. Notably absent from the restrictions were used firearms, with newspapers like the Sycamore, Ill. True Republican shrewdly noting that, because of this, “their value will probably boom.”

The order was explained as a temporary expedient that was necessary to determine the arms requirements for the armed forces and defense production use, and as such the order was narrowed after three months to only apply to “defense rifles, defense pistols and defense shotguns.” The category of defense rifles included any rifle chambered in .30-’06 Sprg., and a selection of .22 cal. rifles deemed suitable for training use. Defense pistols were defined as any .22 cal. H&R “Sportsman” Model target revolvers, and all pistols manufactured by Colt, Smith and Wesson or High Standard.

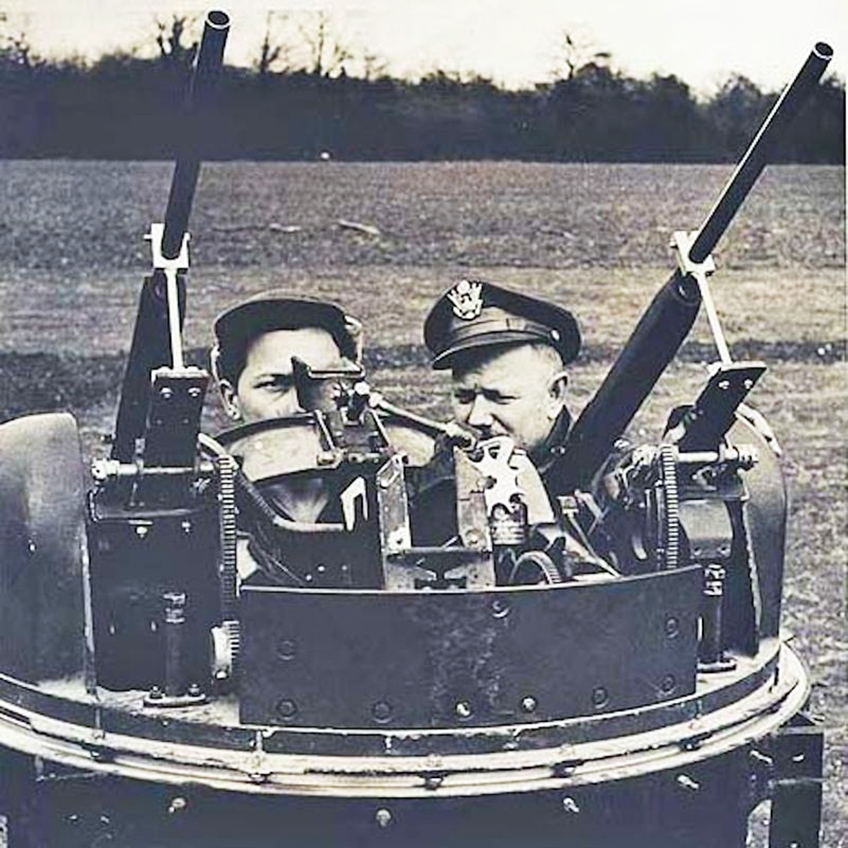

Two Remington Model 11 shotguns mounted into a mock-up twin dorsal turret. This is meant to simulate the dorsal turrets used on many American medium and heavy bombers during World War II, including the B-17 and B-24. The use of 12-ga. shotguns instead of .50-cal AN/M2 machine guns also eliminated the worry of errant rounds in the air during training.

Finally, defense shotguns were all 12-ga., and any semi-automatic or pump-action 16-ga. Again, sales of these outside of the U.S. Government were prohibited with only a few narrow exceptions. One of those, oddly enough, allowed for the sale of designated-defense rifles or shotguns if the net cost to the seller was greater than $72.50 or $45 respectively ($1,169.85 and $726.11 in modern money).

Since the standard Remington auto-loading shotguns fell below that threshold, they were destined for near-exclusive sales to government purchasers. The Sportsman and Model 11 saw their most widespread service far from the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific. The long-barreled variants, sometimes topped with a Cutt’s Compensator, were used for training aerial gunners and anti-aircraft personnel on the concepts of lead and follow-through against moving targets.

A Remington Model 11 set up on an aerial training mount in the bed of a truck. The truck would drive down a course as the trainee engaged targets.

And they weren’t only used for traditional style clay shooting – shotguns were also fixed into contraptions designed to imitate the gun mounts that the aircrew would later use in combat. This gave the students the ability to practice traversing an off-the-shoulder firearm, familiarize themselves with the sight and trigger setups and gain valuable experience—all without having to worry about the enormous safety zones that would be created by firing a .50-cal. machine gun into the air.

And the training wasn’t just stationary, with some students learning to engage moving clays while they were carried along on the back of trucks, playing the part of American bomber aircraft. The “riot gun” variants, with 20” barrels, were mostly destined for another purpose—guard duty. While some certainly made it into front-line combat, the majority of these guns lived a somewhat less exciting—but no less important—life back from the front.

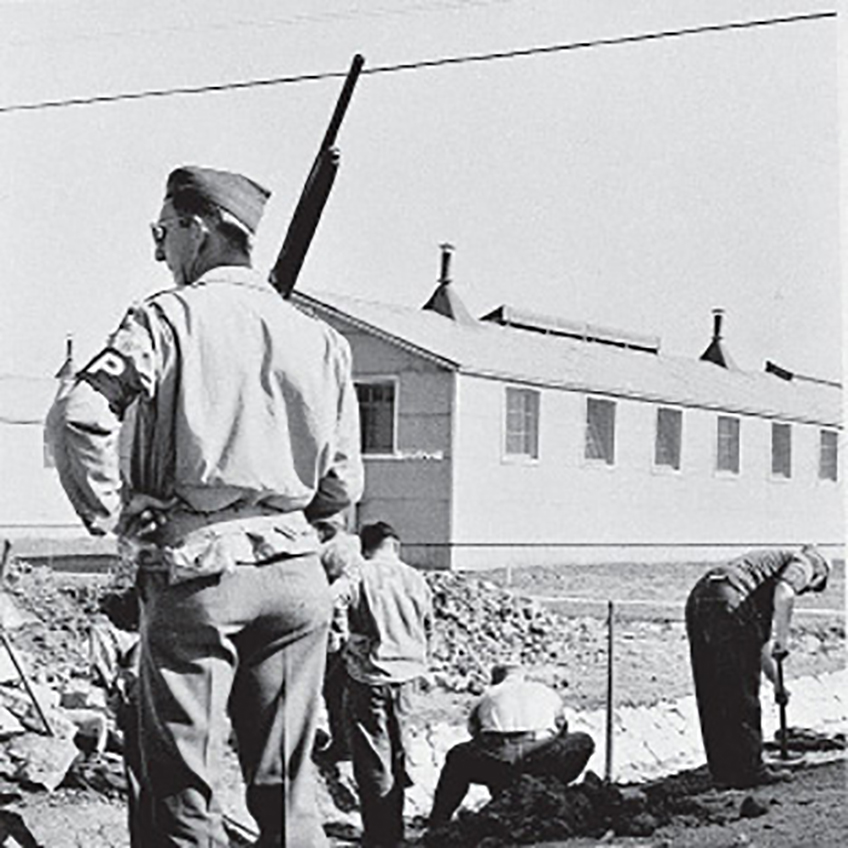

A MP standing guard with a Remington Model 11 in hand.

This ranged from stateside industry protection, to guarding POWs and other prisoners both stateside and abroad. Shotguns of all types were often found in the hands of the newly formed Military Police Corps, officially established in 1941, who valued the shotgun as a tool well suited to managing prisoners and guarding rear areas where errant rifle shots might prove unnecessarily dangerous. One reason we never saw a “Trench Gun” style semi-automatic shotgun during the war may have been because of how the Model 11 operates.

It features a recoiling barrel that would make it largely incompatible with the easy mounting of a bayonet or heat shield. While other recoil operated weapons, such as the M1941 Johnson rifle, overcame this by having a small and lightweight bayonet that would reciprocate with the barrel, it was apparently never deemed important enough to design and field such a system for a long-recoil shotgun like the Remingtons. The pictured Remington Sportsman is one such example of a shotgun originally destined for civilian use that was pressed into service in the months following America’s entry into World War II.

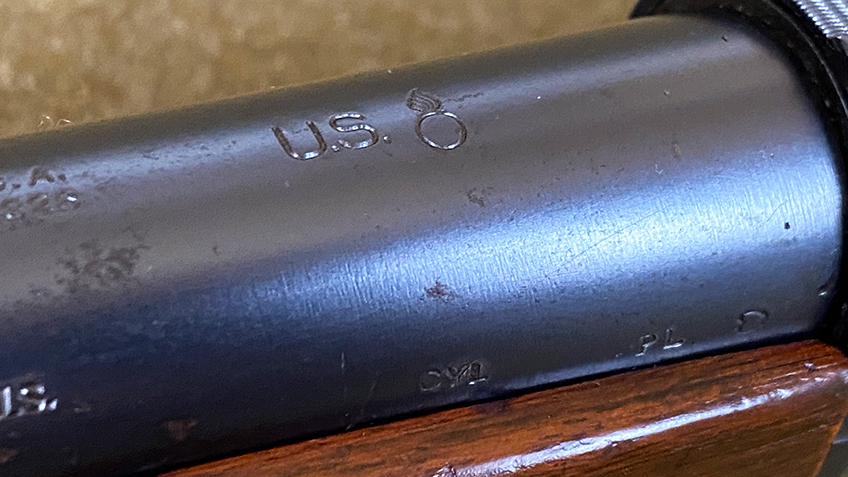

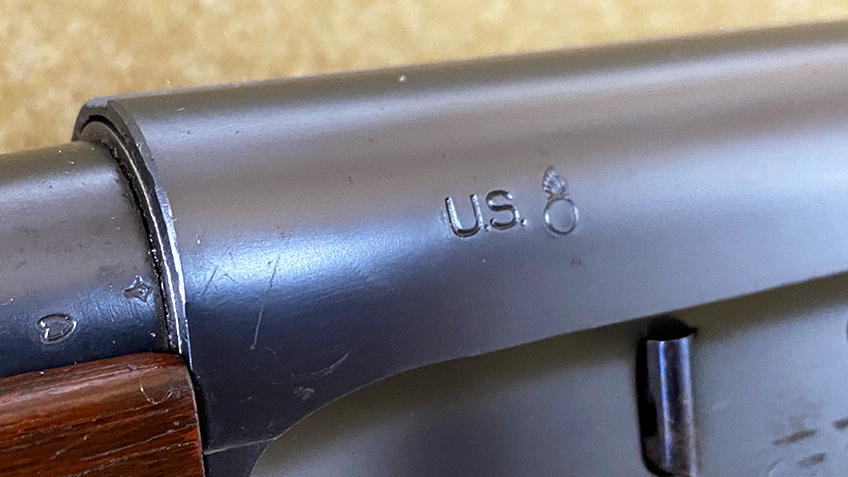

The U.S. Ordnance and other markings on the barrel of the author's Remington Model 11 Sportsman.

It bears a high-polish blued finish, and is neatly roll-stamped with the standard game scenes across either side of the receiver. In contrast to these large embellishments, the US property markings are rather small. On the stock is a faint “Ordnance Wheel” featuring a flaming bomb atop two crossed-cannons and circled by a gunner’s belt. Most also bear an F.J.A. cartouche for Colonel Frank J. Atwood, with a smaller number having an earlier R.L.B. mark instead, for Colonel Roy L. Bowlin.

The metal is marked in two separate places, the left front of the receiver and the top rear of the barrel. Both locations feature a stamped “U.S.” and an Ordnance Flaming Bomb." The standard civilian markings are left in place, including patent information and choke information. All barrels used as riot guns, on both the Sportsman and Model 11, will be marked with “CYLINDER BORE” or “CYL” on the left rear of the barrel ,including a small number where an original choke marking was lined out at the factory, with the cylinder bore status being stamped in its place.

Interestingly, throughout wartime production, Remington retained the 2+1 capacity of The Sportsman even though they were no longer being made with hunting laws in mind, and it wouldn’t have taken much to increase capacity to the 4+1 as found on the Model 11. Perhaps for this reason, or maybe due to existing production capacity, Sportsman riot shotguns are scarcer than their Model 11 riot counterparts. As the war pressed on, existing stocks of pre-war parts quickly dried up.

Newly manufactured parts did away with some of the “frivolous” features found on civilian sporting arms. The duck and pheasant were quick to go, replaced by a plain and smooth-sided receivers. The high polish finish was also replaced with a low-luster blue, and Remington saw fit to prominently stamp such guns with “Military Finish”, presumably in order to indicate to anyone who may come across one at a later date that their civilian shotguns were made to a higher aesthetic standard.

An advertisement from World War II triumphing the use of 12-ga. ammunition used to help train gunners.

Even the checkering on the forearm and buttstock were dropped, despite them actually providing a tangible benefit in combat scenarios. On May 5, 1945, three days before the official German surrender, the War Production Board started the long process of returning to normal by revoking Limitation Order L-55, and releasing their strict control over the types of shotguns that manufacturers could produce.

In late August, after the Japanese war machine lay broken and ready to surrender, the WPB revoked the sections of L-60 relating to revolvers and shotguns. The American sporting shotgun industry was once again free to design, market, produce, and sell its products as it saw fit, and had ready customers in the form of returning G.I.s interested in the shooting sports. The Model 11 and “The Sportsman” are the least expensive U.S. WW2 martial shotguns available on the market today.

With almost 60,000 of all types purchased by the military they don’t have quite the same mystique surrounding them as the more famous “Trench Shotguns”, but they undeniably pulled their weight in a wide variety of roles across the globe during World War II. A collector looking for a military shotgun with a little bit of sporting flair can do a lot worse than an old Sportsman!